On August 13th in 1961 the Berlin Wall was built. I will always remember this day - here is my experience of it:

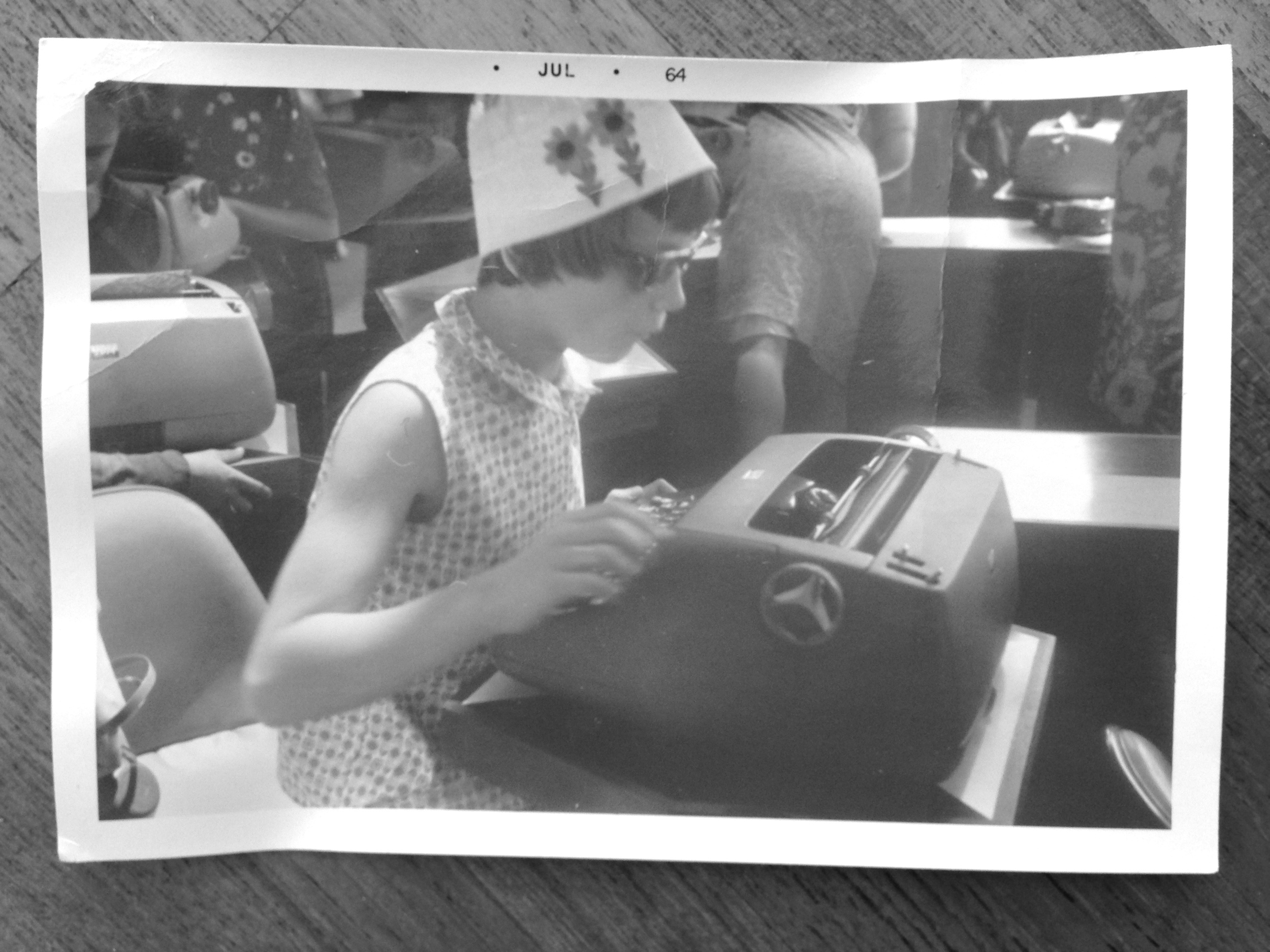

In the living room, men were shouting. Those loud voices had been in my dream as roaring trains. But now I was awake and the men were still arguing next door. Usually I was the first one to wake up but today it was late, the sun beamed a slice of brilliance through a gap in the thick curtains. Why hadn’t my aunt woken me up to fetch Broetchen from the bakery? And why did we have morning guests? Eight years old, I was staying with Tante Maria and Onkel Walter, who were like grandparents to me. Then I realized there were no guests. It was the radio, turned up loud.

“Psst” Onkel Walter brought his finger to his lips when I entered the living room. He was sitting at his enormous desk and behind him, tall dark brown shelves held hundreds of books that smelled like my mother’s leather wallet, only dustier. His face earnest, my uncle pointed to the radio, as if I hadn’t heard it. He always got stern during newscasts, but today something was different and it wasn’t just the volume. Just then, the phone rang, startling me. Onkel Walther bellowed into the receiver louder than the men on the radio. I heard Russen and Amerikaner and Kalter Krieg and I wondered how a war could be cold on such a bright summer day.

Tante Maria, her silver hair pulled back in a twist, came in to see who was calling. She kissed the top of my head and pulled me into the bedroom. “Get dressed, Muckelchen, we’re going out.” Why was she whispering? Why was everything so serious today?

“Where are we going?”

“To find out what’s going on. The Russians have fenced us in.”

“Fenced us in?” I repeated the words.

“Not here. By the Brandenburger Tor.”

Every kid in Berlin knew this landmark. I had been there and I was relieved now because it was far away, in another district. So the fence wouldn’t affect us.

But as soon as we got out on the street, I realized that it already had. Those urgent radio voices blared from every open window. Strangers nodded at each other, their lips unsmiling.

Men in suits and women in dresses had gathered around a newspaper kiosk. Boys in starched white shirts were kicking a ball, girls in pinafores shooting marbles on a strip of dirt. Amazingly, no one was scolding them for getting stains on their Sunday clothes. The adults were shouting and gesturing, shaking their heads, pointing at headlines screaming from sandwich boards. Rolls of barbed wire going through the heart of the city! East German soldiers on the other side! Soviet tanks! Everyone spoke with exclamation marks.

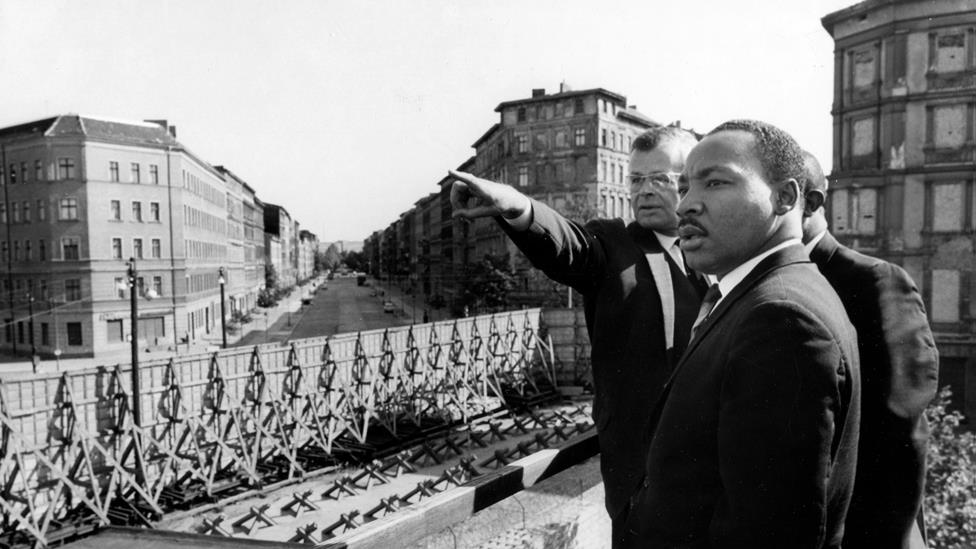

A man with thick-framed glasses said that the barbed wire was just the beginning. “A wall will be built between East and West Berlin, mark my words. People will not be able to cross from one side to the other.”

“You mean we can’t get out?” A woman wearing a wide straw hat shrieked and grabbed her husband’s arm.

Another woman pressed her hand over her mouth. “My mother lives in the East! She’s old and she needs my help.”

“The Russians are taking over!” A white haired man pounded his fist on an invisible table. “I told you they’d find a way to make us pay for the war.” He poked his wife’s shoulder with his finger as if it was all her fault. And then, everyone was talking at the same time.

“How dare they do this?”

“Why don’t the Americans stop them?”

“Maybe they’ve given up on us?” The woman with the hat threw up her hands.

“The Americans would never give up on us. West Berlin is the outpost of freedom, the Frontstadt,” That was Onkel Walter, sounding like he had a direct line to the American Commanders.

Balancing on the lines between the pavement stones, I tried to make sense of things: Russians and Americans didn’t like each other, I knew that. We were somehow caught in the middle because we happened to live in Berlin. Berlin was divided and we were in the Western part. I didn’t know anyone in the East. Once, my father had taken my sister and me over there, to a children’s opera in a fancy old building. But now there were rolls of barbed wire and soldiers were guarding the border. I didn’t have to understand the details of politics to know that this was extraordinary. The warm summer day felt important and somber, like the inside of a cathedral. “A wall will be built and that will be the end of West Berlin!” the bespectacled man boomed again. With his fine hat, he reminded me of my school principal, so I believed him. But I wasn’t afraid. On the contrary, I felt a thrilling excitement. Strangers were talking to each other, even touching each other’s arms. I had an urge to do something heroic. But I couldn’t think of anything. So I took hold of Tante Maria’s hand.

Over the next months, a wall did replace the barbed wire coils and it completely enclosed West Berlin. I saw newspaper photos of workers laying the bricks and soldiers with rifles guarding them. But the wall wasn’t the end of West Berlin. like that man had said, because trains and planes and boats carried supplies through East Germany to our half of the city. East Germans were the ones most affected by the wall; they couldn’t leave anymore. Not for the West, anyway.

(Excerpt from my Memoir in progress)